February 16-17, 1945

The experienced V Amphibious Corps under Major General Harry Schmidt, USMC, had assembled three Marine divisions, the 3d, 4th, and 5th. Schmidt would have the distinction of commanding the largest force of U.S. Marines ever committed in a single battle, a combined force which eventually totalled more than 80,000 men. Well above half of these Marines were veterans of earlier fighting in the Pacific; realistic training had prepared the newcomers well. The troops being assembled were arguably the most proficient amphibious forces the world had seen.

Admirals Spruance and Turner prevailed upon Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith, then commanding Fleet Marine Forces, Pacific, to participate in what became known as Operation Detachment; as Commanding General, Expeditionary Troops. This was a gratuitous billet. Schmidt had the rank, experience, staff, and resources to execute corps-level responsibility without being second-guessed by another headquarters. Smith, the amphibious pioneer and veteran of landings in the Aleutians, Gilberts, Marshalls, and Marianas, admitted to being embarrassed by the assignment. "My sun had almost set by then," he stated, "I think they asked me along only in case something happened to Harry Schmidt."

The physical separation of the three divisions, from Guam to Hawaii, had no adverse effect on preparatory training. Where it counted most—the proficiency of small units in amphibious landings and combined-arms assaults on fortified positions—each division was well prepared for the forthcoming invasion.

The 3d Marine Division had just completed its participation in the successful recapture of Guam; field training often extended to active combat patrols to root out die-hard Japanese survivors.

In Maui, the 4th Marine Division prepared for its fourth major assault landing in 13 months with quiet confidence. Recalled Major Frederick J. Karch, operations officer for the 14th Marines, "we had a continuity there of veterans that was just unbeatable.

In neighboring Hawaii, the 5th Marine Division calmly prepared for its first combat experience. The unit's newness would prove misleading. Well above half of the officers and men were veterans, including a number of former Marine parachutists and a few Raiders who had first fought in the Solomons. Lieutenant Colonel Donn J. Robertson took command of the 3d Battalion, 27th Marines, barely two weeks before embarkation and immediately ordered it into the field for a sustained live-firing exercise. Its competence and confidence impressed him. "These were professionals," he concluded.

Among the veterans preparing for battle were two Medal of Honor recipients from the Guadalcanal campaign, Gunnery Sergeant John "Manila John" Basilone and Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Galer. Headquarters Marine Corps preferred to keep such distinguished veterans in the states for morale purposes, but both men wrangled their way back overseas—Basilone leading a machine gun platoon, Galer delivering a new radar unit for employment with the Landing Force Air Support Control Unit.

[ #9 Al Ferzoco -1935 Mansfield High School Football ]

The Guadalcanal veterans would only shake their heads at the abundance of amphibious shipping available for Operation Detachment. Admiral Turner would command 495 ships, of which fully 140 were amphibiously configured, the whole array 10 times the size of Guadalcanal's task force. Still there were problems. So many of the ships and crews were new that each rehearsal featured embarrassing collisions and other accidents. The new TD-18 bulldozers were found to be an inch too wide for the medium landing craft (LCMs). The newly modified M4A3 Sherman tanks proved so heavy that the LCMs rode with dangerously low freeboards. Likewise, 105mm howitzers overloaded the amphibious trucks (DUKWs) to the point of near unseaworthiness.

The V Amphibious Corps left the Marianas Islands and steamed north / northeast.

Their destination was now revealed to the Marines aboard the ships.

In Japanese, it's name means "Sulphur Island".

It was an ugly, barren, foul-smelling chunk of volcanic sand and rock, barely 10 square miles in size. As described by one Imperial Army staff officer, the place was "an island of sulphur, no water, no sparrow, no swallow." Less poetic American officers saw the resemblance to a pork chop, with the 556-foot dormant volcano Mount Suribachi dominating the narrow southern end, overlooking the only potential landing beaches. To the north, the land rose unevenly onto the Motoyama Plateau, falling off sharply along the coasts into steep cliffs and canyons. The terrain in the north represented a defender's dream: broken, convoluted, cave-dotted, a "jungle of stone." Wreathed by volcanic steam, the twisted landscape appeared ungodly, almost moon-like. More than one surviving Marine compared the island to something out of Dante's Inferno.

This was Iwo Jima.

February 17, 1945

One of the most controversial elements of the Iwo Jima invasion was the extent of the pre-landing bombardment. Marine commanders, whose previous experience had made them painfully aware that considerable time was necessary to find and destroy often-well-hidden Japanese defensive positions, had requested ten days of preliminary shelling. Fifth Fleet commander Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, who had overall responsibility for the operation, knew that time and ammunition supply did not permit such a long bombardment, and also believed, incorrectly, that months of constant attacks by long-range bombers had degraded enemy defenses. He accordingly allowed only three days for the task, and stuck to that allotment despite the Marines' pleas for more.

When Rear Admiral William H.P. Blandy's Task Force 54 arrived off Iwo Jima on 16 February 1945, ready to begin shelling, rain and low visibility made effective gunfire control nearly impossible. Though six battleships (Arkansas, New York, Texas, Nevada, Idaho and Tennessee), five cruisers (Pensacola, Salt Lake City, Chester, Tuscaloosa and Vicksburg) and many destroyers were present and shooting, at the end of the 17th results were modest, at best.

Task Force 54 included Idaho and Tennessee, freshly

returned from overhaul at West Coast navy yards; Nevada, Texas and Arkansas,

veterans of Operations OVERLORD and DRAGOON, and 30-year-old New York,

taking part in an amphibious operation for the first time since TORCH in

1942.

Heavy cruisers Chester, Pensacola, Salt Lake City

and Tuscaloosa (also a European veteran) and the new light cruiser Vicksburg,

with assigned destroyers, completed the gunfire support force.

Admiral Spruance's flagship Indianapolis, together

with battleships North Carolina and Washington, would join on February

19, D-day.

The Battle for Iwo Jima would mark a departure in the

strict government censor of news from the war. Prior to this battle the

government would carefully monitor and stem the flow of news, photos and

print from a battlefield. Everything that would be objectionable or could

possible cause a moral problem (high death tolls, friendly fire, gruesome

photographs, etc..) were banned. There was a week to fourteen days lag

in the news.

But in 1945 there was a growing weariness in the war

by many Americans. People began to question the great sacrifice of lives.

Why didn't we just bomb Japan into surrender? Why did we have to island

hop?

Roosevelt decided to allow cameras and press to accompany

the Marines onto Iwo Jima and report the war directly to the American people.

This action will come into play later with respect to the flag raising

photo.

By 0911 Idaho, Nevada and Tennessee were 3000 yards off the beaches sending heavy direct fire at assigned targets. At 1025 Admiral Blandy ordered them to retire in order to clear the UDT operations, set for 1100. By that time the minesweepers were clear, having swept up to 750 yards of the shore in precise formation, banging away with their own weapons and occasionally coming under fire from the island.

American air forces pounded Iwo in the longest sustained aerial offensive of the war.

"No other island received as much preliminary pounding as did Iwo Jima." --Admiral Nimitz, CINPAC

Incredibly, this ferocious bombardment had little effect. Hardly any of the Japanese underground fortresses were touched.

Twenty-one thousand defenders of Japanese soil, burrowed in the volcanic rock of Iwo Jima, anxiously awaited the American invaders.

The US sent more Marines to Iwo Jima than to any other battle, 110,000 Marines in 880 Ships. The convoy of 880 US Ships sailed from Hawaii to Iwo in 40 days.

It was the largest armada invasion up to that time in the Pacific War.

It would be just 48 hours before Americans would find

out about Iwo Jima.

In just two days a small column would appear on the

front pages of newspapers: "Marines land on Iwo"

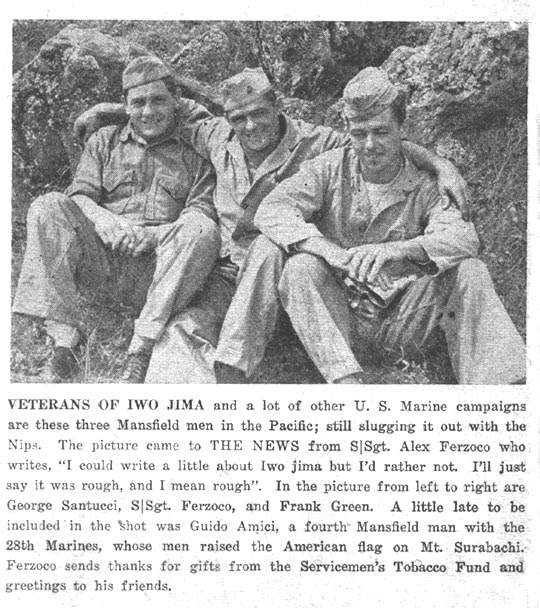

This is how Mansfield began to learn of the Battle of Iwo Jima and the participation of five of her sons: Al Fercozo, George Santucci, Frank Green, Guido Amici, and Guido (Guy) Liberatore.

What was thought to be an easy victory turned out to

be one of the bloodiest battles of the war.

The black volcanic sands of Iwo Jima claimed close

to 30% of all our Marine losses in the war.

The one month battle for Iwo Jima left 6,821 Marines

dead and 20,000 wounded.

Twenty-seven Congressional Medals of Honor were awarded

in the Battle - more than were awarded to Marines and Navy in any other

Battle in our country's history.

But as the first day of shelling came to a close, on

board Admiral Turner's flagship, the press briefing was uncommonly somber.

General Holland Smith predicted heavy casualties,

possibly as many as 15,000, which shocked all hands.

A man clad in khakis without rank insignia then stood

up to address the room.

It was James V. Forrestal, Secretary of the Navy.

"Iwo Jima, like Tarawa, leaves very little choice," he said quietly, "except

to take it by force of arms, by character and courage."

Monday February 19th, 1945

"Mother, you said you were sick. I want you to stay in out of that field and look real pretty when I come home. You can grow a crop of tobacco every summer, but I sure as hell can't grow another mother like you." ----Franklin Sousley Iwo Jima Flag Raiser July 1944, Letter from Training Camp

D-Day

Weather conditions around Iwo Jima on D-day morning, 19 February 1945, were almost ideal. At 0645 Admiral Turner signaled "Land the landing force!"

Battleships and cruisers steamed as close as 2,000 yards to level their guns against island targets. Many of the "Old Battleships" had performed this dangerous mission in all theaters of the war. Marines came to recognize and appreciate their contributions. It seemed fitting that the old Nevada, raised from the muck and ruin of Pearl Harbor, should lead the bombardment force close ashore. Marines also admired the battleship Arkansas, built in 1912, and recently returned from the Atlantic where she had battered German positions at Point du Hoc at Normandy during the epic Allied landing on 6 June 1944.

The massive assault waves hit the beach within two minutes of H-hour. A Japanese observer watching the drama unfold from a cave on the slopes of Suribachi reported, "At nine o'clock in the morning several hundred landing craft with amphibious tanks in the lead rushed ashore like an enormous tidal wave." Lieutenant Colonel Robert H. Williams, executive officer of the 28th Marines, recalled that "the landing was a magnificent sight to see—two divisions landing abreast; you could see the whole show from the deck of a ship." To this point, so far, so good.

Within minutes 6,000 Marines were ashore.

The going became progressively costly as more and more Japanese strong points along the base of Suribachi seemed to spring to life. Within 90 minutes of the landing, however, elements of the 1st Battalion, 28th Marines, had reached the western shore, 700 yards across from Green Beach. Iwo Jima had been severed—"like cutting off a snake's head," in the words of one Marine. It would represent the deepest penetration of what was becoming a very long and costly day.

With grim anticipation, Iwo Jima's Japanese commander,

General Kuribayashi, signaled his gunners to begin to unmasking the big

guns—the heavy artillery, giant mortars, rockets, and anti-tank weapons

held under tightest discipline for this precise moment.

Kuribayashi had patiently waited until the beaches

were clogged with troops and material. Gun crews knew the range and deflection

to each landing beach by heart; all weapons had been pre registered on

these targets long ago. At Kuribayashi's signal, these hundreds of weapons

began to open fire. It was shortly after 1000.

The ensuing bombardment was as deadly and terrifying as any of the Marines had ever experienced. Casualties mounted appallingly.

On the left center of the action, leading his machine gun platoon in the 1st Battalion, 27th Marines' attack against the southern portion of the airfield, the legendary "Manila John" Basilone fell mortally wounded by a Japanese mortar shell, a loss keenly felt by all Marines on the island. Farther east, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Galer, the other Guadalcanal Medal of Honor Marine (and one of the Pacific War's earliest fighter aces), survived the afternoon's fusillade along the beaches and began reassembling his scattered radar unit in a deep shell hole near the base of Suribachi.

Historians described U.S. forces' attack against the Japanese defense as "throwing human flesh against reinforced concrete."

Back in Mansfield, most people who had sons, husbands, fathers serving in the Pacific and especially in the Marines knew something was up. If there was a hint of it in the letters sent home by a home-sick Marine, then the usual agonizing halt of mail always signaled the boys were in harm's way. It had been almost a week without any mail service, and by Tuesday February 20th, the first news of Iwo Jima hit the pages of American newspapers. Radio reports during the evening were beginning to hint that it was a massive battle with growing numbers of casualties.

There were no front lines. The Marines were above ground and the Japanese were below them underground. The Marines rarely saw an alive Japanese soldier. The Japanese could see the Marines perfectly.

Both division commanders committed their reserves early. General Rockey called in the 26th Marines shortly after noon.

Mansfield's Staff Sergeant Alexander Ferzoco, George Santucci and Frank Green were all part of the 26th Marines on Iwo Jima. The 26th Marines was one of the infantry regiments of the 5th Marine Division. It mounted out from Hilo, Hawaii from 1-4 January 1945. Sailing on ships of Transport Division 46, the regiment arrived off Iwo Jima's shores early in the morning of 19 February 1945. The 26th was assigned as the Corps reserve for the initial phase of the assault on Iwo Jima. During the afternoon and evening of D-Day, it landed across the 5th Marine Div's beaches. Beginning on D+1, the 26th Marines began offensive combat operations.

On the football field, there

wasn't too much Alexander 'Al' Ferzoco didn't do. He threw for touchdowns,

ran for scores, blocked, punted and played defense. In the 1937 season,

he led the team to a 7-0-2 season. Mansfield only gave up 32 points, which

is the fourth lowest scored in Mansfield school history. More than one

person had the same observation of Al Ferzoco football skills: "Pound for

pound, Alexander Ferzoco was one of the best football players in Mansfield

High School history". Back during the lazy summer of 1941, many of Mansfield's

boys had decided to join the armed forces in hopes of three square meals

and the promise of an education. Al Ferzoco was one of the first, joining

the Marines. It was decent pay and a good chance to learn some trade.

He was given a big shindig

by the Mansfield gang prior to him shipping out. Everyone was surprised

he got a pretty easy assignment that summer, the Hawaiian islands and a

place called Pearl Harbor. Al was in Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941.

He eventually spent 25 years in the Marines.

Of the six flag-raisers on

Iwo Jima, the story of Harlan Block, in many ways, parallels that of Alexander

Ferzoco.

Harlon Block was born in 1924 in Yorktown, Texas. Harlon was an outgoing daredevil with many friends at Weslaco High School. A natural athlete, Harlon led the Weslaco Panther Football Team to the Conference Championship. He was honored as "All South Texas End." Harlon, and twelve of his teammates enlisted in the Marine Corps together in 1943. Harlon Block was second-in-command. He took over the leadership of his unit when Sgt. Mike Strank (another flag-raiser) was killed.

When his mother Belle saw the Flag Raising Photo in the Weslaco Newspaper on Feb. 25, she exclaimed, "That's Harlon" pointing to the figure on the far right. But the US Government mis-identified the figure as Harry Hansen of Boston. Belle never wavered in her belief that it was Harlon insisting, "I know my boy." No one--not her family, neighbors, the Government or the public--had any reason to believe her. But eighteen months later in a sensational front-page story, a Congressional investigation revealed that it was Harlon in the photo, proving that indeed, Belle did "know her boy."

Early on March 1st, Harlon wrote to Belle, "Dearest Mother, just a few lines to let you know I'm OK. I came through without a scratch...." That evening a mortar blast exploded next to Harlon. The All-State pass-catcher, stood there, let out a muffled scream: "They killed me!" and rolled to the ground dead.

He was 21 years old.

His letter to Belle -saying that he had come through without a scratch -had not yet left the island. It would not be post marked until March 14.

Harlon is buried beside the Iwo Jima Monument in Harlingen, Texas.

By the end of the day, the assault divisions reported

the combined loss of 2,420 men to General Schmidt (501 killed, 1,755 wounded,

47 dead of wounds, 18 missing, and 99 combat fatigue).

Friday February 23rd, 1945

At 8 a.m., on Feb. 23, a patrol of 40 men from 3rd Platoon, E Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, led by 1st Lieutenant Harold G. Schrier, assembled at the base of Mount Suribachi. The platoon's mission was to take the crater at Suribachi's peak and raise the U.S. flag. The platoon slowly climbed the steep trails to the summit, but encountered no enemy fire. As they reached the top, the patrol members took positions around the crater watching for pockets of enemy resistance as other members of the patrol looked for something on which to raise the flag.

At 10:20 a.m., the flag (54" x 28") was hoisted on a steel pipe above the island. This symbol of victory sent a wave of strength to the battle-weary fighting men below, and struck a further mental blow against the island's defenders.

Lusty cheers rang out from all over the southern end of the island. The ships sounded their sirens and whistles. Wounded men propped themselves up on their litters to glimpse the sight. Strong men wept unashamedly. Navy Secretary Forrestal, thrilled by the sight, turned to Holland 'Howlin Mad" Smith and said, "the raising of that flag means a Marine Corps for another five hundred years."

Forrestal was so taken with the fervor of the moment that he decided he wanted the flag as a souvenir. "The hell with that!" muttered Colonel Chandler Johnson when news reached him. The flag belonged to the Marine Battalion. He dispatched Lieutenant Ted Tuttle to the beach to scare up a replacement flag. "And make it a bigger one", he called, after Tuttle scrambled off.

When the 2nd Platoon of Easy Company returned from a patrol, Captain Dave E. Severance, the commander of Company E, 2d Battalion, 28th Marines, ordered them up the mountain. Just then Tuttle hurried into view. He was carrying an American flag obtained from LST-799. As it happened, this flag, which was 96" x 56" was a good deal larger than the one planted on the mountain. It had been found in a salvage yard at Pearl Harbor and rescued from a sinking ship on that day that will live in infamy.

It was a Navy tradition to present flags that had flown around Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941 to various warships as they were commissioned or refitted for duty from Hawaii. This is how this second flag got to Iwo Jima. This tradition continues today as many Naval war vessels now serving in the waters around the Middle East, carry flags that were flying in New York City and at the Pentagon on September 11th, 2001.

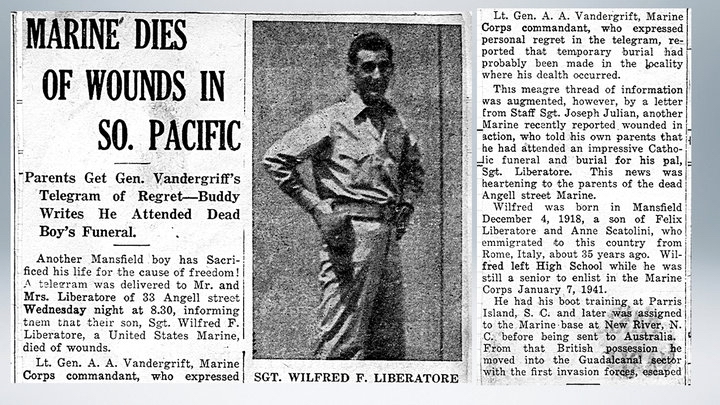

Of the five Mansfield boys on Iwo Jima, the last two: Guido Sherino 'Squinky" Amici was in the 28th Marines and Guido 'Guy" Liberatore was in the 26th Marine Division. Corporal Guido Liberatore lost his life on Iwo Jima on March 4th, 1945. Guido was awarded the Purple Heart. Guido Amici was with Guido Liberatore when he died.

There was a Western Union office in Mansfield and it was staffed by one man: Roy Foster Martin, who later became the town's Fire Chief. Roy had the job of delivering those telegrams to the families of those in the military who were wounded, dead or missing. The sight of Roy, off to get a priest or minister to accompany him on a call, was enough to send a shiver up the back of anyone witnessing his brisk walk out from his office.

Not once, or twice, but three

times Roy knocked on the front door of the Liberatore home in Mansfield.

Staff Sergeant John Liberatore, an Army veteran, serving in the European

theater, was killed in action, in France, during the autumn of 1944. Upon

learning the news, Guido had enlisted in the Marines to avenge his younger

brother's death. Wilfredo 'Ozzie' Liberatore, now a veteran of Guadalcanal

and Saipan had died in the Pacific.

All three sons of the Liberatore's were now lost and Mansfield was in shocked silence.

Soon, two of the Liberatore

sons were shipped back to Mansfield for interment at Saint Mary's Cemetery.

Guido Liberatore was interred in Hawaii's 'Punchbowl' cemetery after the

war. The town turned out to mourn it's fallen sons.

During the funeral, the father

Felix Liberatore, overcome with grief at the lost of this three sons, suffered

a heart attack. Helped to his car, he lingered at St. Mary's Cemetery long

enough to hear taps being sounded. Taken home, he lapsed into unconsciousness

and died. The Italian community and Mansfield had little time to recover.

The word 'Liberatore' in Italian

means --'to free the oppressed; to liberate'

The six men of the 2nd Platoon of Easy Company , who participated in the second or "famous" flag raising on Mount Suribachi were composed of five Marines, joined by a medical corpsman. They were Sgt Michael Strank; Pharmacist's Mate 2/c John H. Bradley, USN; Cpl Harlon H. Block; and PFCs Ira H. Hayes, Franklin R. Sousley, and Rene A. Gagnon.

Mike Strank was born in 1919 in Jarabenia, Czechoslovakia. He was described by many as a Marine's Marine and that alone says it all. He was their leader and Sergeant. It was Mike who got the order to climb Mt. Suribachi. Mike picked his "boys" and led them safely to the top. Mike explained to the boys that the larger flag had to be raised so that "every Marine on this cruddy island can see it." It was Mike who gave the orders to find a pole, attach the flag and "put'er up!"

Mike's right hand is the only hand of a flag raiser not on the pole. His right hand is around the wrist of Franklin Sousley, helping the younger man push the heavy pole. This is typical of Mike, the oldest of the flag raisers, always there to help one of his boys. Two months before the battle Mike's Captain tried to promote him but Mike turned it down flat: "I trained those boys and I'm going to be with them in battle," he said. Mike died on March 1, 1945. He was hit by a mortar as he was diagramming a plan in the sand for his boys. Mike is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Franklin Sousley was born on Sept. 19, 1925 in Hilltop, KY. Franklin was a red-haired, freckle-faced "Opie Taylor" raised on a tobacco farm. His favorite hobbies were hunting and dancing. Fatherless at 9, Franklin became the main man in his mother's life. Franklin enlisted at 17 and sailed for the Pacific on his 18th Birthday. All that's left of Franklin is a few pictures and two letters Franklin wrote home to his mother: Franklin was the last flag raiser to die on Iwo Jima, on March 21 at the age of 19. When word reached his mother that Franklin was dead, "You could hear her screaming clear across the fields at the neighbor's farm." Franklin is buried at Elizaville Cemetery, Kentucky.

Ira Hayes was born on January 12, 1923 Sacaton, Arizona.

Ira Hayes was a Pima Indian. When he enlisted in the Marine Corps, he had

hardly ever been off the Reservation. His Chief told him to be an "Honorable

Warrior" and bring honor upon his family. Ira was a dedicated Marine. Quiet

and steady, he was admired by his fellow Marines who fought alongside him

in three Pacific battles. When Ira learned that President Roosevelt wanted

him and the other survivors to come back to the US to raise money on the

7th Bond Tour, he was horrified. To Ira, the heroes of Iwo Jima, those

deserving honor, were his "good buddies" who died there. At the White House,

President Truman told Ira, "You are an American hero." But Ira didn't feel

pride. As he later lamented, "How could I feel like a hero when only five

men in my platoon of 45 survived, when only 27 men in my company of 250

managed to escape death or injury?"

In 1954, Ira reluctantly attended the dedication of the Iwo Jima monument in Washington. After a ceremony where he was lauded by President Eisenhower as a hero once again, a reporter rushed up to Ira and asked him, "How do you like the pomp & circumstances?" Ira just hung his head and said, I don't." Ira died three months later after a night of drinking. As Ira drank his last bottle of whiskey he was crying and mumbling about his "good buddies." Ira was 32.

George Santucci was one of Mansfield's better athletes. He starred in both football and baseball but it was baseball that he loved most. For years after the war he told his family that all he did during the war was play baseball. For decades, whenever the conversation came up about the war, George would just say, "All I did during the war was play baseball, I never saw any action."

He had his own way to cope with what he saw on Iwo Jima.

One relative said that one day he sat with George and asked again about the rumors that George was on Iwo Jima. George emphatically stated he was never on the island. When the relative showed him a Mansfield news clipping (see above) of George, with Al Ferzoco and Frank Green on Iwo Jima, George just stared at the newspaper article for awhile.

Finally he said, "Oh, yeah I was on Iwo Jima, but all I did there was play baseball.

That was George Santucci.

Rene Gagnon was born in Manchester, N.H. on March 7,

1925. He was the youngest survivor and the man who carried the flag up

Mt. Suribachi. He was the first survivor to arrive back in the US. Rene

was modest about his achievement throughout his life.

Rene is honored with a special room in New Hampshire's

prestigious Wright Museum. Rene Gagnon died in Manchester, N.H. on October

12, 1979. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, the Flag Raiser

buried closest to the Marine Corps Memorial.

John Bradley was born on July 10, 1923 in Antigo, WI. "Doc" Bradley was a Navy Corpsman who "just jumped in to lend a hand." He won the Navy Cross for heroism and was wounded in both legs. Bradley, a quiet, private man, gave just one interview in his life. In it he said . . ."People refer to us as heroes--I personally don't look at it that way. I just think that I happened to be at a certain place at a certain time and anybody on that island could have been in there--and we certainly weren't heroes--and I speak for the rest of them as well. That's the way they thought of themselves also."

John Bradley returned to his home town in the Midwest

after the war, prospered as the owner of a family business -a funeral home,

and gave generously of his time and money to local causes. He was married

for 47 years and had eight children. While Bradley had a public image as

a war hero, he was a very private person. He avoided discussion of his

war record saying only that the real heros were the men who gave their

lives for their country. The Global Media reported the death of a World

War II icon on January 11, 1994 at the age of 70. But his hometown newspaper

best captured the essence of Bradley's life after the war: "John Bradley

will be forever memorialized for a few moments action at the top of a remote

Pacific mountain. We prefer to remember him for his life. If the famous

flag raising at Iwo Jima symbolized American patriotism and valor, Bradley's

quiet, modest nature and philanthropic efforts shine as an example of the

best of small town American values."

Mansfield's Guido Sherino 'Squinky' Amici and John "Doc" Bradley shared a common link after the war. Both men ran a funeral home in their home towns. The Amici Funeral Home on Main Street in Mansfield was a family run business for many decades before it was recently sold to Michael Bolea.

People who knew 'Squinky' in Mansfield said he was a 'walking history book'. He always had a way of making you feel good when you were down. Sherino had a great sense of humor. While working in the local carpenter's union, he would pull out a measuring tape and begin measuring a friend and then say: "I have a casket just your size".

Every time Squinky drove by a nice old large house he would say, "What a beautiful Funeral Parlor that would make." He passed out cards to his friends to carry in their wallet just in case something happened. It told how to contact him for the body.

Once you knew Sherino Amici,

you became one of the family.

By noon, the platoon was on the summit, taking down the first flag and preparing to unfurl the second.

AP photographer Joe Rosenthal missed the first flag raising. He wasn't going to miss this second opportunity. He had hastily joined the platoon and lugged up with him his cameras and film.

As Rosenthal noted in his oral history interview, ". . . my stumbling on that picture was, in all respects, accidental."

When he got to the top of the mountain, he stood in a decline just below the crest of the hill with Marine Sergeant William Genaust, a movie cameraman who was killed later in the campaign, watching while a group of five Marines and a Navy corpsman fastened the new flag to another piece of pipe. Rosenthal said that he turned from Genaust and out of the corner of his eye saw the second flag being raised. He said, "Hey, Bill. There it goes." He continued: "I swung my camera around and held it until I could guess that this was the peak of the action, and shot."

It was the last shot on the roll and Rosenthal thought he missed it.

He quickly reloaded and called for a group shot. The men of the platoon poised under the flag in what became known as the 'Gung-Ho' shot.

Rosenthal took 18 photographs that day, went down to the beach to write captions for his undeveloped film packs, and, as the other photographers on the island, sent his films out to the command vessel offshore. From there they were flown to Guam, where the headquarters of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet/Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas, was situated, and where the photos were processed and censored.

"Here's one for all time!" exclaimed John Bodkin, the AP Photo Editor in Guam.

Later, when asked if the photo was posed, Rosenthal, not knowing that his now famous photo had come out, said "yes, it was posed"; thinking of the 'Gung-Ho' shot.

Saturday's newspapers reported the worse news possible

on Iwo Jima.

3,650 Marines were dead, wounded or missing after

only two days of fighting.

These were more than all the causalities on Tarawa.

These were almost as many on Guadalcanal in five months

of jungle combat.

This was worse than Anzio or Normandy.

It was the bloodiest battle for the Marines since

Gettysburg.

Americans recoiled in shock and horror.

On Sunday, Joe Rosenthal's photo ran across newspapers

in America.

Millions of Americans were transfixed by the image.

People would always remember where they were when

they saw the photo.

It became the iconic photograph of the Second World War.

It is the most reproduced photographic image in the world.

The previous four part notes are from various sources:

The Marine Archives on-line,

Flags of Our Fathers, by

James Bradley,

Various television documentaries

on Iwo Jima,

Letters from Mansfield historian

Roger Thayer,

Correspondence with relatives

of the Mansfield boys.

My interest in Iwo Jima probably

began when I was just 7 or 8.

I recall seeing this photo

in my father's scrap book.

My father was flipping through

the pages while we were in the attic and I saw him pause, look down and

say......."Now they were heroes.."

I found it rather odd to think

my father had a hero.

It was different than how

he talked about the Great DiMaggio.

These guys were obviously

his friends.

Maybe it was the funny sounding

name.....Iwo Jima..

or just a boys fascination

with soldiers, big boats and loud guns...

But I read everything I could about Iwo Jima.....and the war in the Pacific.

When I was older, I began

to appreciate more the sacrifice....and the honor...

and later how there truly

are ...Sacred Places...