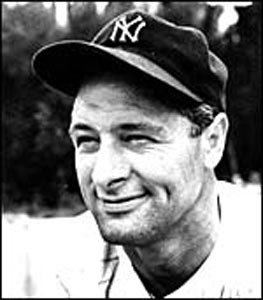

Lou Gehrig was born June 19, 1903.

To fully appreciate the legacy that Henry Louis Gehrig left behind,

one truly has to look at the beginning, the middle and the end.

The beginning was over 100 years ago, on June 19, 1903, in New York,

where a baseball team now known as the Yankees was playing its

inaugural season.

A 14-pound boy, a Big Apple indeed, was born in Manhattan’s

Yorkville district to German immigrants Heinrich and Christina Gehrig.

“Little” Lou would be the only one of their four children to survive

past infancy; one died before him and two after him.

The middle was a majestic baseball career with those Yankees that

yielded 493 home runs, 13 consecutive 100-RBI seasons, a .340 career

average, six World Series championships and an unthinkable streak of

2,130 consecutive games played. The Babe got the headlines; the Iron

Horse just got it done.

The end was in 1939, a paradox of a lifetime. A giant of a baby, a

giant of a ballplayer, known in the beginning and the middle for his

persistence, health and staying power, Gehrig was diagnosed with a

degenerative muscle disease that the Mayo Clinic reported to the Yankees

that summer as “amyotrophic lateral sclerosis”. With the most famous

speech in sports, Lou Gehrig, barely 36, bade farewell to all on that

last Fourth of July at Yankee Stadium. Within two years, he was gone.

But never to be forgotten.

Model of consistency “Gehrig was a guy who went out there and

enjoyed playing the game,” Colorado Rockies first baseman Todd Helton

says today. “He went out there and played as long and as hard as he

could. I go out there and play every day, even if something is bothering

me because you never know when the game, or even life itself, gets

taken away.”

“Day in, day out, he typified back then what today’s Yankees think

of as Yankees, a guy going out and playing hard every single day, making

no excuses,” adds Tino Martinez, one of those who later filled Gehrig’s

shoes at first base in the Bronx. “He just knew how to play the game.”

The average person has a great admiration for someone who quietly

and passionately goes about his job every day and every year, and we saw

that just last year. MLB.com

users determined that the Most Memorable Moment in Major League history

was when Cal Ripken Jr. broke Gehrig’s consecutive-game record.

That speaks volumes about what Gehrig meant to the game. His

consistency was something that even he had taken for granted while he

was building a streak that became his biggest statistical achievement.

In Frank Graham’s 1942 biography, “Lou Gehrig: A Quiet Hero,” there is a

story that bears this out. In 1933, while the Yankees were in

Washington, Dan Daniel of New York’s World-Telegram asked Gehrig in a

hotel lobby: “Do you know how many games you have played in a row?”

Gehrig shook his head. “No, I don’t. Come to think of it, it must

run up in the hundreds somewhere.” Told that it was roughly 1,250 at

that time, then 57 away from the record set by former Red Sox and

Yankees shortstop Everett Scott in 1925, Gehrig said: “Gosh! Why I never

thought of that.. I had no idea.”

Daniel then asked Gehrig the obvious question: “What do you play

ball every day for, anyhow? Why don’t you take a day off once in a

while?”

It was the only way Gehrig knew. He proceeded to tell a story about

when he was in grammar school and was ill one morning. His mother had to

work as the Gehrigs tried to eke out a living, and before leaving for

her job she “said I would have to stay in bed.” Lou went to school after

she left, and later that day his mother had to go to the school to pull

him out and bring him back home. “I never had missed a day in school

and I felt I just had to be there,” he said. “I guess it’s . . . well . .

. just like me. . . . The way I’ve always been and, I guess, the way

I’ll always be.”

It was that way ever since Gehrig replaced Wally Pipp as the

Yankees’ starting first baseman that day in 1925, and only the ALS could

take him out of the lineup. Look at Gehrig’s career stats for games

played. The total was 2,164. That means that all but 34 were in

consecutive fashion, and you can chalk those up to his early days of

breaking in as a bench player. His career was nearly a complete streak.

Life in the shadow

Gehrig first appeared with the Bronx Bombers late in the 1923

season, at a time when Babe Ruth and America were roaring. In ‘25, when

Gehrig joined the Sultan of Swat as a regular, opponents braced for what

would become the most feared back-to-back hitting combination to this

day. The Yanks were the first pro sports team to wear jersey numbers,

making it easier for broadcasters to identify, and the numbers

represented their spot in the batting order. Ruth was No. 3 and Gehrig

was No. 4.

Ruth was the flamboyant slugger, basking in the spotlight and living

life as hard as he belted fastballs. Gehrig was the model of

consistency, around the clock.

He had slashing power, spraying homers to all fields, and he was

only happy to work in a relative shadow. Consider what happened at the

1932 World Series in Chicago. Ruth hit his “Called Shot” homer there off

Cubs pitcher Charlie Root, and the legend has only grown over time.

Does anyone remember that Gehrig proceeded to homer off Root in the next

at-bat while Wrigley was buzzing? Or that Ruth and Gehrig already had

gone deep together earlier in the same game?

In his 1990 biography, “Iron Horse: Lou Gehrig In His Time,” Ray

Robinson called them the “odd couple.” He wrote that “there was too much

difference in temperament and character for a firm bond of friendship

to have formed.” But there certainly was mutual respect, and right from

the start.

Yankees manager Miller Huggins walked Gehrig out toward the batting

cage in the rookie’s first day in The Show, and Gehrig had not brought

along a favorite bat of his own on that nickel Subway ride to the

stadium. So he innocently picked one out from a bunch of bats that were

resting against the cage.

Unbeknownst to Lou, it was the Babe’s favorite, all 48 ounces of it.

Gehrig used that bat to whack BP pitch after pitch into the bleachers,

traditionally only Ruth’s area of reach. Ruth might have told anyone

else to leave that bat alone; all he said to the rook that day was:

“Hiya, keed.”

There was room for both in the Yankee lineup, and room for both in

great Major League lore. There always still seemed to be runs to drive

in. That’s one of the amazing things about Gehrig’s career numbers. He

hit behind Ruth and (later) Joe DiMaggio, two fabulous base-cleaners,

and yet his RBI numbers were consistently through the roof. Gehrig drove

in 184 runs in 1931, still an American League record.

Just think about that 1927 season. Gehrig’s home run number bulged

to 47, and only Ruth ever had hit more. Gehrig’s RBIs soared to 175, a

record at the time, and even more astounding when you consider that he

stepped to the plate 60 times after congratulating Ruth on having just

cleared the bases.

What might have been Gehrig is generally considered one of the 10

best Major Leaguers of all-time, and it is fascinating to wonder what

might have happened had a disease not stolen the rest of his career.

Let’s stop for a moment and play what-if.

Gehrig entered that final 1939 season with a streak of 2,122

consecutive games played. He had said he thought 2,500 was an attainable

goal. Had he remained healthy, it is reasonable to assume that no one

in the Yankee organization would have stood in the way of that. Assuming

the Yanks played the full 154-game schedule from 1939-41, Gehrig

already would have reached that goal by the time Japan bombed Pearl

Harbor.

Conservatively speaking, it would have been reasonable to project

another 500 hits, 350 runs, 90 doubles, 30 triples, 100 homers, 350 RBIs

and 300 walks in those three years. He would have passed Ty Cobb as the

all-time leader in runs scored. He would have been around the 600-homer

mark. He would be the all-time leader in RBIs, not Hank Aaron. Gehrig

might have been right behind the Babe again, as usual, as subsequent

generations of fans debated the best of all-time.

Although Gehrig would have been 38, past draft age, those who knew

Lou say he probably would have volunteered for the Navy at the start of

World War II.

So those three seasons probably would have been it. And then,

perhaps in the mid-’40s, Yankee Stadium might have seen a Lou Gehrig

Appreciation Day.

Instead, of course, Gehrig’s fans were watching Gary Cooper star as

him in “Pride of the Yankees,” one of the most-watched sports movies.

Muscles were only part of the reason for Gehrig’s phenomenal

baseball career. In the end, when ALS rendered those muscles

increasingly useless, his courage and inspiring approach to life were

still there. And so were his fans.

Graham wrote in that 1942 biography: “He left the shining legacy of

courage.” Randy Wolf, the current Phillies pitcher, is among those who

will never forget. “Gehrig didn’t feel sorry for himself,” he said. “He

lived up to who he is. He was an American hero. That’s why his farewell

speech will always be known.”

[By Mark Newman / MLB.com 6/18/2003]

Lou Gehrig’s Farewell Speech:

“Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about the bad

break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of

this earth.

I have been in ballparks for seventeen years and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans.

“Look at these grand men. Which of you wouldn’t consider it the

highlight of his career just to associate with them for even one day?

Sure, I’m lucky. Who wouldn’t consider it an honor to have known Jacob

Ruppert? Also, the builder of baseball’s greatest empire, Ed Barrow? To

have spent six years with that wonderful little fellow, Miller Huggins?

Then to have spent the next nine years with that outstanding leader,

that smart student of psychology, the best manager in baseball today,

Joe McCarthy? Sure, I’m lucky.

“When the New York Giants, a team you would give your right arm to

beat, and vice versa, sends you a gift - that’s something. When

everybody down to the groundskeepers and those boys in white coats

remember you with trophies - that’s something. When you have a wonderful

mother-in-law who takes sides with you in squabbles with her own

daughter - that’s something. When you have a father and a mother who

work all their lives so you can have an education and build your body -

it’s a blessing. When you have a wife who has been a tower of strength

and shown more courage than you dreamed existed - that’s the finest I

know.

“So I close in saying that I may have had a tough break, but I have an awful lot to live for.”